In 2005, I went to war. I fulfilled a lifelong dream and started working for an international charity that provided medical and mental health services in conflict-affected countries. I was elated, filled with pride at putting on the official t-shirt that now represented who I was. I was a Humanitarian, off to serve, support and help others. I went with such excitement, convinced that this was what I was meant to do, and how I wanted to live my life going forward.

So began a 12 year journey of living in conflict zones while battling with the one playing out inside myself. Trauma lives in our bodies; it hides away and visits us when we least expect it. It comes up in our dreams, our memories, our thoughts and our actions. It colours our choices and prevents us from being clear about what we need.

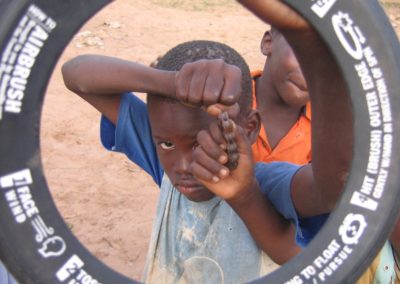

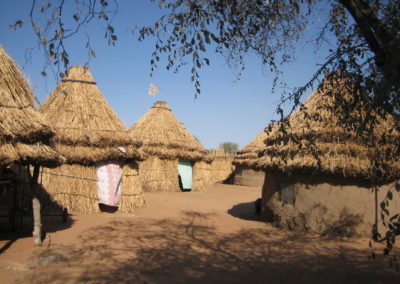

For the first few years, I gathered traumatic experiences like badges to be proud of. I lived through bombs, robberies, fighting and witnessed unimaginable suffering. It’s hard to know what was ‘the worst’, but one experience has stayed with me. I was working in a hospital in the Central African Republic and a young girl in the feeding centre wasn’t getting better. She would sit and stare at the wall, as would her mother. Not interacting with each other. Not moving. I was working with local counsellors and we began to ask more questions. It turned out that the girl and her mother had witnessed all of the children in her village being forced into a grass hut and burned alive by the Janjaweed (a militia group that operates in Western Sudan and Eastern Chad). We visited the village, saw the burned skeleton of the hut and the graves and with that came a profound feeling of hopelessness in humanity. How could a human being do this to children? Through talking with the mother and her daughter and doing counselling, we were able to support them and they left the hospital physically healthy, but I often think about them. They were going back into the jungle, into poverty and conflict. What happened to them?

Despite all of this, war zones felt ‘right’. I felt comfortable in a way that I didn’t understand. It ticked the right boxes: helping others, putting someone else’s needs first, witnessing and something even deeper that I found difficult to name. Then addiction set in. It wasn’t addiction to drugs or drinking, but addiction to adrenalin and risk. I was constantly seeking my next ‘fix’. Central African Republic, Darfur, Iraq, South Sudan. With each assignment, as I became more and more exhausted, I would dream of going home to do…something else, something calmer. But home was foreign. I didn’t feel ‘at home’ at home anymore. It was like being on the other side of the glass looking in at other people’s lives. When I was at home, at first I was exhausted and wanted to rest and then I couldn’t wait to go out again. I’d start to scan the job ads, catch up on the latest humanitarian crisis and begin to assemble my backpack. My life didn’t fit ‘normal’ anymore, but war zone to war zone certainly wasn’t the answer.

I had a vague sense of self-destructiveness, that living with a constant adrenalin rush, moving countries each year because contracts are short term, and never having a home wasn’t healthy. But what was the answer? The problem was complex. The work was the most interesting, dynamic and rewarding that I’d ever done. I loved going to parts of the world where few others ventured. At the same time, the trauma and the stress took its toll. I felt tired much of the time, increasingly detached from my work, feeling that the need and suffering were just too overwhelming. They were classic signs of burnout, but I didn’t know what to do.

I did therapy, took courses, looked at how to manage stress and build resilience, tried to find something that would help me to do the work without harming myself. In the end, my husband and I decided to come home but there was still a sense of restlessness. I was trying to come to terms with who I was and where I belonged. My work started to focus on assisting other aid workers and on finding the key that would help us all. Many people who work in areas where they witness terrible suffering have the same feelings. Is it possible to work in situations of intense trauma without harming yourself?

Then I found Hoffman. When I did the Process I began to understand where my patterns of behaviour were coming from and why I was so drawn to humanitarian work. I grew up in a home where it was very important to help others, to always be available to someone in need and to put your own needs second. This helped to explain why I had chosen a profession where I helped others, but it still didn’t explain the attraction to conflict.

The ‘A-ha!’ moment that the Process gave me was insight into why I was so attracted to adrenaline. It was as a result of several childhood experiences that paired high adrenaline experiences, danger, and approval. In that moment I understood that going to conflict zones was reinforcing childhood patterns of a desire for love and approval interplayed with danger.

Through Hoffman, I’ve found a deep healing, an understanding of my patterns and why I’m drawn to the work that I do. I feel now that I can do the work from a place of compassionate detachment. I can work with others without taking on their suffering as my own and without harming myself. Hoffman has brought me a reconnection with myself and a renewed energy for my work. I feel that I can be playful, find joy and re-engage with my vision as well as new tools to keep myself on track. The path that keeps me connected to my creativity, my strengths, and my dreams.

Karen is featured in the 2018 issue of Hoffman magazine. To order a FREE copy for yourself, friends or family, click here.

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman