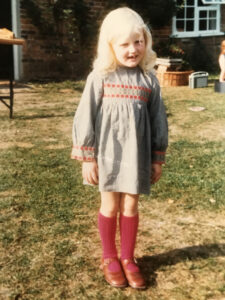

When I was five, I was painfully, quiveringly shy. So shy that I took up residence in the airing cupboard, where I would immerse myself in the soft, clean laundry and sing to my family of twenty-two teddies and dolls from around the world; tragic operettas involving lovelorn knights and Chinese princesses and orphans drowned in the Caspian Sea. To the outsider, my childhood seemed idyllic – homes in Chelsea, Berkshire and the south of France, private school, pets from Harrods, and glamorous parents who drove sports cars and threw lavish cocktail parties – but deep down inside, my little blonde heart was filled with dread.

When I was five, I was painfully, quiveringly shy. So shy that I took up residence in the airing cupboard, where I would immerse myself in the soft, clean laundry and sing to my family of twenty-two teddies and dolls from around the world; tragic operettas involving lovelorn knights and Chinese princesses and orphans drowned in the Caspian Sea. To the outsider, my childhood seemed idyllic – homes in Chelsea, Berkshire and the south of France, private school, pets from Harrods, and glamorous parents who drove sports cars and threw lavish cocktail parties – but deep down inside, my little blonde heart was filled with dread.

Born the youngest of five daughters to a mother who craved a son, the airing cupboard became my safe haven – away from my anxious, insecure father, my mother, overwhelmed with the stress of bringing up five daughters, and the stern au pairs who came and went. It also offered protection from my lonely older sister who would terrify me by dressing up as the wicked witch from Snow White in order to punish me for choosing the company of my dolls over her.

Being a hypersensitive child, I was often overwhelmed by feelings of grief that left me exhausted and confused. On my sixth birthday, when I was taken to see the Walt Disney film Dumbo, I sobbed so intensely that I had to leave the cinema. Then one day, when I was about eight, my grandmother told me that I had a twin who had died in my mother’s womb, and I finally understood the source of my tears. I remember the words granny used to describe my twin’s death: ‘fossilised in the placenta.’ I didn’t understand what those words meant but they sounded scary and sad. Later, when I told my sisters about my twin, with a sense of pride that I was one of a pair, one of them said “You probably sucked the life out of him.” Even though this comment was made in jest – wit being a highly prized commodity in my family – and doubtless I even laughed along, it seeded within me a core belief that I was destructive and guilty.

Soon after that incident, I lobbied my mother to be allowed to go to boarding school. The day I arrived there I made a conscious decision to dry my tears and adopt the role of a clown – a role not yet taken by my other sisters – in order to distance myself from the bad person I believed I was.

At the end of my first term, I returned home for the school holidays a different person – confident, funny and a million miles from the sad little girl in the airing cupboard. In my teens I became a rebellious tomboy, adopting the masculine traits of leadership, competitive wit and aggression, and by the time I reached my 20’s I was genuinely off the rails, pretending to my parents I was attending the university I’d enrolled at, whilst indulging in a whirlwind lifestyle of drugs, nightclubs, unsuitable lovers and dangerous escapades. Typical of someone with trauma in their psyche, I was out to prove to myself and the world that I was indeed destructive and guilty.

At the end of my first term, I returned home for the school holidays a different person – confident, funny and a million miles from the sad little girl in the airing cupboard. In my teens I became a rebellious tomboy, adopting the masculine traits of leadership, competitive wit and aggression, and by the time I reached my 20’s I was genuinely off the rails, pretending to my parents I was attending the university I’d enrolled at, whilst indulging in a whirlwind lifestyle of drugs, nightclubs, unsuitable lovers and dangerous escapades. Typical of someone with trauma in their psyche, I was out to prove to myself and the world that I was indeed destructive and guilty.

At the age of 23, I finally plucked up the courage to audition for drama school and after I graduated, I performed on the London stage but lacked the emotional stability to handle the uncertainty inherent in the acting profession. The years passed and I married, founded a business, and had children, but my mental health was marred by unresolved anger towards my mother and sister, manifesting in damaged relationships and abandoned projects. I dreamed of writing comedy, but my creative flame was easily snuffed out by lack of self-belief and besides, the role of writer in my family was already spoken for.

When my husband asked me for a divorce, plunging my heart into despair, a voice within me whispered ‘time to do the work’ and I remembered a friend telling me about how doing the the Hoffman Process had saved her marriage.

I arrived at Florence House full of fear but determined not to use humour to avoid being vulnerable in the group. There was too much at stake for me to sabotage this opportunity.

From the very first day, I felt safe enough to remove my clown mask and re-connect with the inner child I had tried so hard to bury. In return she taught me to see the value in feeling my feelings in order to heal my childhood wounds rather than doing everything possible to anaesthetise them by drinking too much, avoiding situations where I wasn’t in control and courting conflict rather than peace.

From the very first day, I felt safe enough to remove my clown mask and re-connect with the inner child I had tried so hard to bury. In return she taught me to see the value in feeling my feelings in order to heal my childhood wounds rather than doing everything possible to anaesthetise them by drinking too much, avoiding situations where I wasn’t in control and courting conflict rather than peace.

Towards the end of the week I’d learnt a variety of techniques to soothe myself whenever these feelings arose and I finally began to see myself reflected in others as compassionate and kind rather than destructive and guilty, so much so that my mantra on departing was ’I deserve my place in the group’.

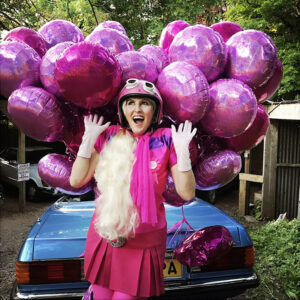

Since leaving Hoffman, my marriage has recovered, and I am finally taking my creativity seriously. I won a prestigious international TV scriptwriting competition with the sister I thought I could never forgive, I am now a professional stand up comedian, where I perform as both myself and the myriad of characters that live in my head, some of them dating back to the airing cupboard! I have written and produced cabarets, a one woman show, a radio comedy series and I currently have a TV script in development.

But the greatest gift that Hoffman has given me is deep sense that my twin is smiling down upon me, and cheering me on, every step of the way.

Top Tips for Finding Your Creative Voice

1. Remember what you loved doing as a child and re-visit that passion.

2. Record each sabotaging thought and counter-argue in the positive.

3. Give yourself a deadline to complete your first project.

4. Meditate every morning on your creative goal, imagine yourself in the act of doing what makes your heart sing and succeeding at it.

5. Find your champions, people who will help you realise your dream. Be bold and ask for help, learn from successful people in your chosen field.

To see Rose’s work, visit her website: www.rosewadham.com

|

|

|

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman