In many ways my younger brother and I had an idyllic and stable childhood growing up by the sea in Barry, South Wales. There was a strong community – families in our local area were always in and out of each other’s homes and I still have friends there to this day. We both knew from the outset that we were adopted as babies and were very much wanted. Despite this, I always had a sense of something in the background that I couldn’t quite put my finger on that caused me disquiet. All the evidence pointed to me being very loved, yet I felt there was something missing, a disconnect.

In many ways my younger brother and I had an idyllic and stable childhood growing up by the sea in Barry, South Wales. There was a strong community – families in our local area were always in and out of each other’s homes and I still have friends there to this day. We both knew from the outset that we were adopted as babies and were very much wanted. Despite this, I always had a sense of something in the background that I couldn’t quite put my finger on that caused me disquiet. All the evidence pointed to me being very loved, yet I felt there was something missing, a disconnect.

Mum adored children and wanted to be with us as we were growing up. She was highly intelligent but came from a disadvantaged background which didn’t allow her academic opportunities. She taught me to read when I started nursery school and I was lucky enough to walk across the park each day to an excellent local school which I really enjoyed.

My father began his working life as a mechanic. His passion was engineering and innovation and he went on to become the technical director of a large international company, which meant he was often away and had offices in London. I loved going up to London with him and eventually ended up taking my Law degree there.

My parents were very generous with their time, both to those closest to them and in the community, always wanting to help. It was from them that I got a strong sense of justice, of fairness and a desire to advocate for the powerless and those who don’t have a voice.

But again, there was that disconnect – having these wonderful supportive parents who could not have done more to show me how much I was wanted and valued – yet I still had that feeling something vital was missing. I felt almost that I wasn’t entitled to feel the way I did. This feeling which I couldn’t understand or articulate would affect the way my life developed – outwardly successful but inwardly conflicted.

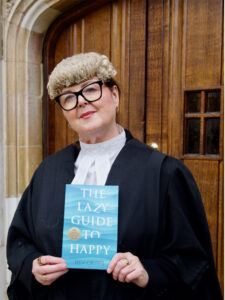

In 1988 I was called to the Bar and started a fulfilling legal career. As time went on, I often conducted the most serious cases. Throughout that time, I was struck by the number of people whose lives had been blighted by earlier experiences – often from childhood. Of course, in my professional capacity there was nothing I could do but it got me thinking: why, through no fault of theirs, did these people have to carry that burden for such a long time after the events had passed?

In 1988 I was called to the Bar and started a fulfilling legal career. As time went on, I often conducted the most serious cases. Throughout that time, I was struck by the number of people whose lives had been blighted by earlier experiences – often from childhood. Of course, in my professional capacity there was nothing I could do but it got me thinking: why, through no fault of theirs, did these people have to carry that burden for such a long time after the events had passed?

I’ve always been fascinated with the mind and personal development, though I’d never investigated therapy. Looking back, I wonder if I was trying to find answers to this problem that had plagued me from childhood,

On top of the stressful work life, my father, who had had his first heart attack when I was 11, was increasingly suffering the effects of heart disease. Though he was the epitome of resilience and embraced life with huge energy and sheer force of will, his health was always on my mind, I remember one of a number urgent calls in the middle of the night, to come to Wales when I was halfway through a case where a child witness had just given evidence. Happily, he survived that event and I returned to the trial the next day. However it took a long time for me to appreciate the toll this lifestyle was taking on me.

Fast-forward to 2013. By now I was working for the Crown Prosecution Service which meant a heavy caseload, mainly of murder trials. My then partner was a serving soldier on his third tour of Afghanistan. In the space of that one year, my best friend was diagnosed with cancer which sadly was terminal; my former partner ended the relationship and my father finally lost his battle with heart disease and died in November. After the relationship ended, I’d also moved to the south coast of England, which meant a long commute to my chambers and court.

After my father died, I was very concerned about my mother, so I frequently drove the long journey back and forth to Wales. It felt like I was spending my life on the road. When someone drove into the back of my car, it was the last straw. I went to see my GP, as I had neck pain and insomnia. He asked me if I had any stressors, and as I detailed the above, I saw his eyes widen. When he suggested I needed to take time out, I replied jokingly that I’d scheduled a breakdown for Christmas. But even seeing how intense my life had become through the eyes of a professional, I continued on regardless, not knowing there was any other way forward.

After my father died, I was very concerned about my mother, so I frequently drove the long journey back and forth to Wales. It felt like I was spending my life on the road. When someone drove into the back of my car, it was the last straw. I went to see my GP, as I had neck pain and insomnia. He asked me if I had any stressors, and as I detailed the above, I saw his eyes widen. When he suggested I needed to take time out, I replied jokingly that I’d scheduled a breakdown for Christmas. But even seeing how intense my life had become through the eyes of a professional, I continued on regardless, not knowing there was any other way forward.

Finally, I remember a wellbeing pundit on the car radio saying that despite the difficult circumstances currently in the news, we had agency and control over our responses to these. I laughed hollowly, but it sowed a seed that eventually led me to the Process. The Hoffman Process had been on my radar for a while; I knew a colleague had done it and an acquaintance had recommended it. I’d never experienced anything akin to therapy but I really feared my life was becoming unsustainable and something would happen if I carried on the way I was.

I gave in my notice to the Crown Prosecution Service to enable me to go back to being an independent barrister. It so happened that my final day at the CPS was the day before I started the Process and it was at the end of my part in difficult child exploitation case. I did wonder if I was too tired for the course, but I could see that this was a lifelong pattern of being busy and if I didn’t interrupt it, nothing would change until I made myself ill.

For a long time before the Process, I’d felt overwhelmed, rushing from pillar to post. I felt so stretched, like there were no boundaries and I was stuck in a repetitive cycle. Not only had I figuratively lost my way but, when I drove myself to the Process, I literally did. I got lost and could not see the ‘right road’. I very nearly turned it into a sign that I shouldn’t go!

When I got to the venue, it felt like I’d been through a war. I was exhausted. I saw that same emotion mirrored on some of the faces of my group as we gathered for the first time, apprehensive about what the Process would entail but eager to start. Once the week got underway, all my anxiety fell away. It was a safe space.

When I got to the venue, it felt like I’d been through a war. I was exhausted. I saw that same emotion mirrored on some of the faces of my group as we gathered for the first time, apprehensive about what the Process would entail but eager to start. Once the week got underway, all my anxiety fell away. It was a safe space.

Previously I’d tried to intellectualise or think my way out of the feelings that had plagued me throughout my life, but the gift of Hoffman for me was that I could finally connect emotionally to that and was able to articulate what had been ailing me. One of the most significant moments was when I was able to inwardly communicate with my birth mother as part of a visualisation and, as bizarre as it seems, it came into my consciousness that I also had a birth father – something I’d never reflected on before – which really expanded my understanding of my feelings about my adoption. The exercise we did allowed me to truly connect with my birth parents and deepened my understanding of them.

Overall, the Process gave me a new insight into my emotional life. I realised my ceaseless desire to help and keep pressing onwards was a way of masking my inner turmoil. My Process group formed a WhatsApp group and we’re still in contact all these years later. We’ve been in each other’s lives through births, marriage, personal triumphs and tragedies and the sad death of an amazing friend, who was part of our group. For many Process grads, Hoffman offers a real sense of community that’s offered a safety net in difficult times.

A year after the Process, I did a follow up course called the Q2 over a long weekend, which I really recommend. As well as consolidating and expanding my knowledge of the Hoffman tools, it gave me another important insight and the facilitator suggested I might benefit from one-to-one therapy. After that I saw a therapist weekly for over a year and dealt with my grief at the loss of my father and saw how that had ignited negative feelings around adoption.

I was grateful for my association with Hoffman again in 2020 when we went into lockdown. My mother, who had had a heart attack the August before, developed dementia and died just before Christmas 2019. I’d taken those months away from work and needed a break. I’d remained in Wales to close the house up ready for sale when Covid hit. I was there alone, having got Covid myself. It was quite a test of my own resilience. I started developing routines and habits to support my own wellbeing and Hoffman was an integral part of that. The Institute began offering free daily morning check-ins and regular webinars. My own Process group organised meet ups on Zoom. All of this gave my life a structure and support that was really important for my mental health at such a stressful time.

It’s my intuitive response and, I later found out, a fundamental element of resilience, that I have to get something positive out of the worst of times. When my father was in his last months, I wrote a treatment for a TV series, which had a character dedicated to him. After my experiences during Covid, I started to qualify in modalities that would mean I could help people move forward in their lives and also effect change quickly. The idea of helping people in this positive way had been in my mind since I completed the Process. I’d seen and experienced how there can be post-traumatic growth. I’m now a licensed resilience trainer, twice-certified positive psychology coach, clinical hypnotherapist and NLP practitioner. As a barrister I’ve seen how people who have survived the worst possible events have used their experiences to help others. I want to make sure that they and anyone who has suffered negative experiences have got the tools to not only survive but thrive and be happy.

It’s my intuitive response and, I later found out, a fundamental element of resilience, that I have to get something positive out of the worst of times. When my father was in his last months, I wrote a treatment for a TV series, which had a character dedicated to him. After my experiences during Covid, I started to qualify in modalities that would mean I could help people move forward in their lives and also effect change quickly. The idea of helping people in this positive way had been in my mind since I completed the Process. I’d seen and experienced how there can be post-traumatic growth. I’m now a licensed resilience trainer, twice-certified positive psychology coach, clinical hypnotherapist and NLP practitioner. As a barrister I’ve seen how people who have survived the worst possible events have used their experiences to help others. I want to make sure that they and anyone who has suffered negative experiences have got the tools to not only survive but thrive and be happy.

I’ve distilled my research and coaching system into a book called The Lazy Guide to Happy which was launched on the anniversary of the 35th year of my call to the Bar. The book is aimed at people with many commitments, who think that happiness and wellbeing are a ‘nice to have’ but they have no time. It contains low effort evidence-based tools which can be fitted in to the busiest of days to enhance wellbeing and happiness together with an explanation of why they work.

You can find out more about Bev’s Training and Coaching at: mybcconnection.com

To order The Lazy Guide to Happy, click here

Bev’s Top Three Happiness Tools

I’ve been asked what are the three most effective tools you can easily implement in your busiest days to ensure you have a solid base upon which to build your wellbeing and happiness levels, so here are my top three – all evidence-based.

- Bookend your days. In the morning, have a glass of water when you get out of bed every day without fail. Acknowledge and congratulate yourself that you’re doing it. It seems so trivial and yet for the really burned-out, this is something that can be managed no matter what the circumstances. It’s not the water – though always drink lots – it’s knowing there are very small things you can do, no matter what’s happening around you, to be consistent and have the confidence to move on to other things and grow. Broaden and build by taking action. Add to the glass of water by spending the first 5 minutes of the day quietly, without any tech – these moments of calm are for you before you become the subject of everyone else’s demands.

- At the end of the day, just before you go to sleep, write down three good things that have happened to you today and why. This, of all the positive psychology interventions, is my favourite. Writing provides you with a record – something to look back at after a frantic week. We’re primed to look for the negative and often lose the good experiences in the daily busy-ness. On a bad day, it could be simply that it didn’t rain, or someone smiled at you in a queue, and on a good day, it may be your greatest triumph. Gratitude has almost become a cliché, but the key to mental health has often been described as having agency and gratitude This intervention was trialled in a huge study in the US military amongst the senior non-commissioned ranks and had a 4.9/5 approval rating. Done last thing at night, it primes your subconscious for a positive night. It’s lovely to do as a bedtime ritual with younger children and – with teen anxiety on the rise – is great to do with them too. If drill sergeants can be persuaded to do this, then there’s hope that they can too.

- Finally, and if you only do one thing, do this; take microbreaks throughout your day. Try and get somewhere quiet and close your eyes, shutting out as much of the outside world as you can. Take a minute where you do nothing more than concentrate on your breathing. Sometimes the only available place to do this is in the bathroom, however these little breaks are so valuable – they can get even the busiest and most time-pressured of us through the longest days.

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman