Doing the Process to sort out some ‘family stuff’? Emma Macpherson got more than she bargained for when she was asked to attend the Hoffman Process for a magazine feature.

Doing the Process to sort out some ‘family stuff’? Emma Macpherson got more than she bargained for when she was asked to attend the Hoffman Process for a magazine feature.

Nearly 20 years ago, I headed to Florence House in Sussex, to check out the Hoffman Process. As far as I was concerned, it was just another course that might improve one’s life for a week or two. It ended up becoming part of my life. Not just in the way it transformed family relationships, or because countless family and friends followed my lead and did the Process after me, but also because now, with my husband Matthew Pruen, we run Hoffman Retreats at our home in France and relationship workshops for Hoffman in France and London.

Central to Hoffman is the concept of ‘patterns’ – the behaviours, belief systems, moods, attitudes and insecurities that we unconsciously adopt from our caregivers as children in order to be loved. Looking back, my most significant moment on the Hoffman Process was an exercise where we stood in the shoes of our 12-year-old parents. That exercise transformed my understanding of my parents’ lives and how it shaped them. I could see how both their fathers going away to fight in the Second World War had impacted my mother and father, and how the patterns that had developed as a result had, in turn, impacted me. Dad had been sent to boarding school aged 3 when his father died, whilst my mother, to escape the bombs in London, had been sent to a children’s home before she was 2. ‘Intergenerational trauma’ is a phrase we hear a lot about now, but back then I just knew the fear and sense of abandonment they must have suffered, because in spite of the care I was given, it’s a pattern that comes up for me too.

When I ‘met’ my 12-year-old parents on the Process, their stiff upper lips were already firmly in place. Both were brave little soldiers, both at boarding schools a very long way from home. It put my life into perspective. I could see what they had given me and done for me, against incredible odds. It also made me want to know more about their lives and what had shaped them. After I left the Process, I started asking them questions, putting together the family tree and researching our family history.

Family history is one of the most researched topics on the internet. DNA testing to find our relations and discover who we are is fuelling the fastest-growing area of medical research. As our families and communities become increasingly fractured, it seems the human need to know where we belong intensifies.

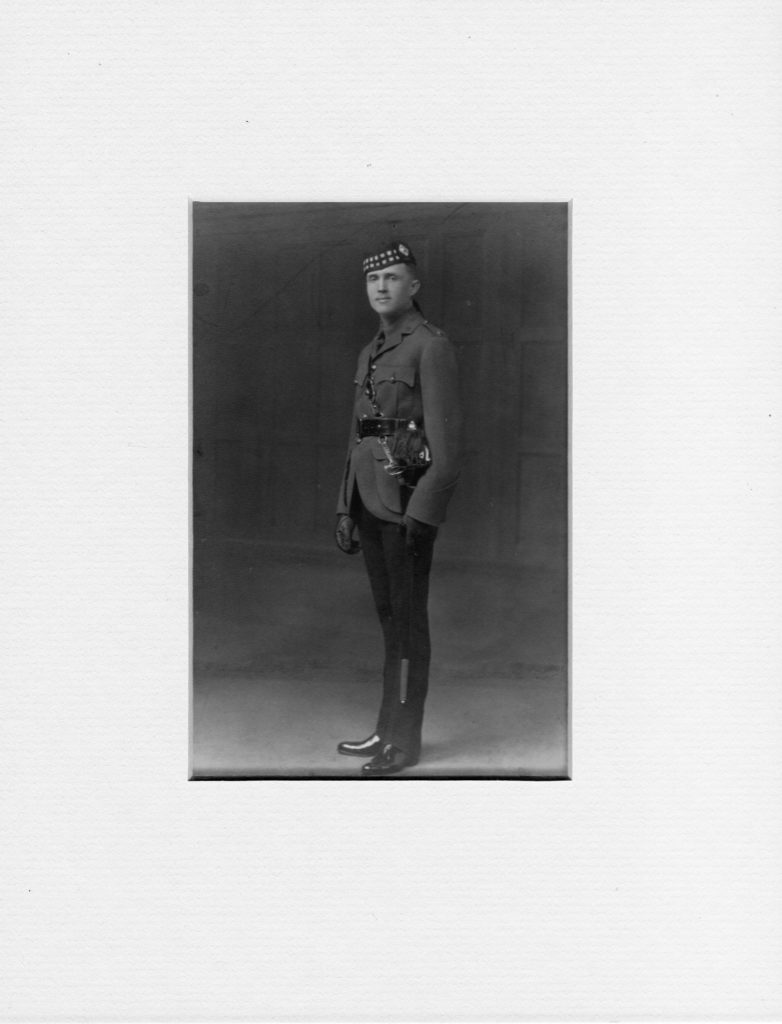

To commemorate what would have been my unknown paternal grandfather’s 100th Birthday, I decided to make my own version of the TV programme Who Do You Think You Are. As my grandfather had been killed when my dad was so young, we knew nothing about him. I started researching and filmed myself crossing the UK to visit the place of his birth, his school, the church he married in and his army regimental museum. To my distress and delight, I even found a picture of his grave in Hong Kong.

Going to his old school and being shown pictures of this unknown grandfather as a boy was incredibly moving. I could pick him out in a black and white rugby team photograph immediately; he didn’t look a bit like Dad but he was the image of my nephew. Exactly one hundred years after his own father was born, without having any awareness of what the date signified, my dad sat down and learned the stories of his father’s life for the first time. He melted.

As I researched my grandfather’s life, I discovered that his father – my great grandfather – was also a soldier who had been away fighting a war while his son was growing up. A pattern emerged of fathers either dying early or going away to war – or both – throughout my male line. Seeing this transformed my judgement of Dad, from being an emotionally absent man who sent me to boarding school at 11, to viewing him as a hero. He broke the mould of his male line; throughout my childhood he came home every evening after work. He was present in a way no-one before him had been able to be. At 80 years old, he has also lived longer than any of them as far back as I can tell.

As I researched my grandfather’s life, I discovered that his father – my great grandfather – was also a soldier who had been away fighting a war while his son was growing up. A pattern emerged of fathers either dying early or going away to war – or both – throughout my male line. Seeing this transformed my judgement of Dad, from being an emotionally absent man who sent me to boarding school at 11, to viewing him as a hero. He broke the mould of his male line; throughout my childhood he came home every evening after work. He was present in a way no-one before him had been able to be. At 80 years old, he has also lived longer than any of them as far back as I can tell.

Occasionally there are patterns we struggle to link to either parent, or issues that don’t appear to have an identifiable root. They can be the result of family secrets, but can also belong to relations whose stories have become lost.

There is a scene in the Closure ceremony on the Process where we imagine cords going from ourselves to our parents and back to their parents. It made me realise that we can carry patterns not just from our parents, but also from our past generations. Through work like Hoffman, I believe we are doing sacred work, not just in healing ourselves but our ancestral line.

I love the various Facebook genealogy groups where I see people becoming obsessed with one particular ancestor, only to discover they share similar stories. We see on programmes such as ‘Who Do You Think You Are’ that people unwittingly move to the same city, or even street, of an ancestor who had been written out of the family story. Or careers come up again and again. I attribute my first jobs in the rag trade – constantly on the train to visit factories in Manchester – my sister going into the fashion industry as a photographer and my niece studying fashion design to my recently-discovered, female ‘Lancashire Cotton Mill’ line. These stories have a way of being heard lest we forget them.

For some it’s not so fortuitous; we can see threads of trauma, abuse or intense poverty running though the female line in just the same way.

Hoffman graduate Gaye Donaldson is a highly accomplished practitioner of a therapy called Systemic Constellation Work, which deals with these issues. I have attended a few Constellation workshops post-Process and have found them quite miraculous for getting to the crux of some of these really deeply entrenched family patterns.

Gaye says, ‘Whilst we each have our own personal history we are also, inevitably, deeply connected with our wider family history which exerts a strong, and often unacknowledged, influence over us. Exploring this connection or ‘entanglement’ through the lens of Systemic Constellation Work can offer remarkable insight and illumination which bring qualities of strength, and then resolution, that enables us to move on.

‘The constellation process supports us to hand back, with great respect, the trauma of previous generations of our family, so that we can be free to live our own life purpose.’

Matthew trained with Gaye and others in this methodology and it’s something which has informed some of the exercises included in the Hoffman French Retreat.

Whilst the Hoffman Process was devised by Bob Hoffman, I think he intuitively understood so many other healing systems. There are echoes in the more spiritual areas of the Process of ancient wisdom, of healing work we might loosely call shamanic.

About 10 years ago I took a Shamanic Practitioner training and was delighted to discover the mysterious sounding ‘Shamanic Drum Journey’ was similar to some of the visualisations we do on the Process. At the same time, the ‘Medicine Wheel’ slotted very beautifully into the Hoffman model of our Quadrinity, the four aspects of self – emotional, physical, intellectual and spiritual. The training gave me another way to access information and healing for me and for my ancestral family, and it is something we’ve also included in the Hoffman French Retreats.

One of the reasons I love the Process so much and continue to recommend it to people is that it draws on something much wider and more holistic than so many other courses. It’s not just educational or therapeutic, but it’s also soul work, helping us find our way home to our selves. And being at home in ourselves, finding our place in our family, and in our community is, I believe, the essence of the sense of belonging so many of us yearn for.

Emma and Matthew run regular Hoffman relationship workshops for couples and individuals. For details, click here.

For other courses at their gorgeous home throughout the year, visit: https://www.retreat.fr/

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman

Sign up to receive monthly newsletters from Hoffman